From the sprawling city of Lima, Peru, to the bustling boroughs of New York City, assistant professor of sociology Dr. Katherine Maich’s research led her to explore the lives of domestic workers around the world. Years of research, listening and learning led her to write her new book, Bringing Law Home, published Aug. 5 by Stanford University Press.

With a Ph.D. in sociology, Maich has long centered her research on the relationships between law, gender, labor and inequality. Her latest book is the culmination of two years of comparative ethnographic research in two countries, examining the employment of domestic workers and the legal and social frameworks that influence their lives.

The idea for her research sparked early in life, as she knew she wanted to pursue the topic of domestic workers. Through her comparative research and new book, she hopes to shine light on often unnoticed domestic workers- those who cook, clean and care for others in their homes.

Maich’s research examines how differences in labor laws, social customs and the workplace shape the treatment of domestic workers around the world. She hopes her book will show the need for new rights and legislation to support those who are often invisible outside of the domestic industry.

“I wanted to look into the laws that were passed to protect domestic workers, and how to actually bring those laws home and give those workers the rights and protections they deserve, specific to the home itself,” Maich said. “I think the more attention we have on these workers, the better,” Maich said. “Making informal work more formal and more protected is better for everyone.”

Maich carefully selected New York City and Lima for their noticeable similarities. Both Lima and New York City are seen as political administrative centers in their respective countries. The two cities share similar population sizes, are both very densely packed and are historic sites of migration flows. However, despite these similarities, New York City and Lima both have unique histories that have differently shaped their social structures.

Creating Connection in Lima and New York City

The research began in Lima. New to the city, Maich immersed herself in the community through exploration with her research assistant Victoria Maraví, a linguistics student from the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru.

The two spent most of their time at a community center for household workers, who were often also new to the city and seeking connections and resources. They joined workshops hosted at the center on basic skills used in the home, culinary lessons in traditional Peruvian meals, and labor rights.

“We would prepare the meals in groups of over a dozen people, eat together and experience a sense of community,” she said. “Recipes were shared so workers could use them for potential employers.”

Outside the center, Maich spent the majority of her time exploring parks and other highly congregated areas, in conversation with people willing to share their stories.

“Once I built rapport and trust, workers were more open to interviews,” she said. “My outsider status was beneficial because people were curious, which made them more open to speaking with me.”

New York City offered a new environment with different challenges for Maich to explore. KC Wagner, director of workplace issues at Cornell University’s Worker Institute, allowed her to participate as a visiting scholar with an office based in Manhattan. After locating housing and learning the rules of engagement, she began conducting interviews with workers throughout the five boroughs. She met with domestic worker groups and organizations in the city, which connected her with workers willing to be interviewed. Maich was surprised that people in Lima were much more willing to talk than the New Yorkers; thus, the research took longer than expected.

After collecting these stories, she shared them through comparative ethnography research conducted between the two cities.

“I was a messenger, building a connection and solidarity between the two research sites,” she said.

A Need to Clean House

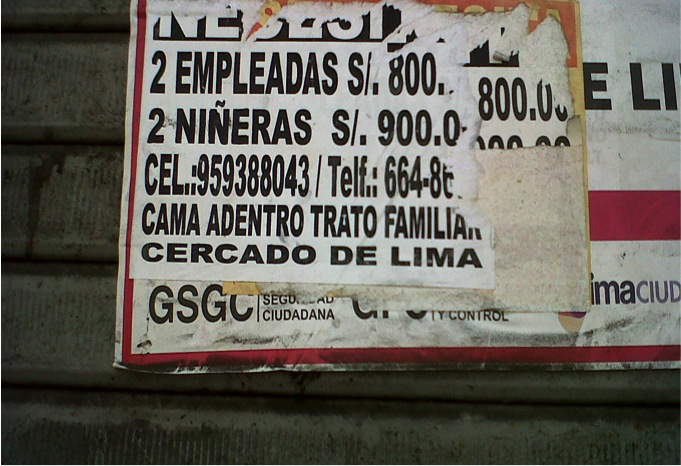

Throughout her research, Maich found that Peruvian law only extends domestic workers half of the labor protections granted to other occupations.

“A key difference that I found fascinating was the practice of having a maid, nanny or several domestic workers who would cook, clean and care in your home was kind of expected in Lima. It is much more normalized compared to the US,” Maich said. “In Lima there are many more indigenous migrants who come in from the outskirts of the country to work for Peruvian employers, creating sort of an internal industry versus a more external migration.”

Maich also discovered in New York City that the laws there grant negligible protections and deliberately avoid language around immigration.

“The population in New York is this heterogenous group of immigrant workers coming from several different countries working for a homogeneous group of employers, who are mostly dual-income upper-middle class,” Maich said.

Part of her research recognized that the history of coloniality is deeply embedded into the modern relationships between employers and domestic workers and plays a role in today’s understanding of power, domination and inequality in the home and workplace.

“Throughout the book I ask, ‘Can we legislate vulnerability away,’ as the entire book underscores the limits but also the promises of legal reform,” Maich said. She hopes historic, precedent-setting laws live on in practice to shape working conditions and possibilities for both individual resistance as well as collective activism...These laws aren’t perfect, but they are important. Laws can truly enable workers to reimagine themselves, their lives and their futures.”

A Labor of Love

Maich’s experiences continue to shape her life and teaching. She reveres her students at Texas A&M and the chance to bring her experiences into the classroom.

“I love being at Texas A&M,” she said. ‘The students are amazing and the environment that the university offers is an exciting place to be as faculty; I have research support and an opportunity to combine my teachings with my research here.”

Going forward, Maich is excited for the opportunity to continue her research here in Texas, as she continues to shape the ways in which society treats domestic workers.

"There is so much rich research to be done in this area,” she said. “I hope my work may influence people to think differently when hiring a nanny, housekeeper or babysitter. A small change in consciousness and respect for domestic workers would be exciting to see.”