Editor’s note: This story is part of an occasional series about the impact of Title IX.

Andrea Abat ’89 still remembers how she felt the first time she saw the Fightin’ Texas Aggie Band perform.

It was the fall of 1984, her senior year at Houston’s Memorial High School, and she was visiting a friend at Texas A&M: “I just had one of those cloud-parting, dove-descending moments,” she recalls, and from that moment on, she was determined to join their ranks.

The next year, Abat and two of her classmates became the first women admitted to the band after a 90-year history as an all-male unit.

“Going in, I had no preconceived notions about breaking barriers or anything like that. I just wanted to be part of this amazing band and what they did,” Abat said. “Until I got to the Quad in the fall of 1985, I wasn’t really aware of what was happening and what a huge change it was going to be for the university.”

Ultimately, it was one in a long series of changes in the Corps of Cadets set in motion by the 1972 federal law that sought to eliminate discrimination on the basis of sex in higher education. It was added as an update to Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which applied only to discrimination in employment.

But even in a post-Title IX world, there was still plenty of work to be done. Abat said she will always be grateful to the many courageous women who helped clear her path to the north end of Kyle Field.

“It’s wonderful to be somewhere in that chain,” said Abat, who went on to serve as an engineer in the U.S. Army, a special agent for the Environmental Protection Agency and now a director for the Carnival Corporation’s Incident Analysis Group. “And it’s very gratifying now to look out across a sea of cadets and see plenty of women in positions of leadership.”

Changing Times

Women were officially allowed to enroll at Texas A&M as full degree-seeking students in 1963, thanks to President James Earl Rudder’s decision to integrate the university along racial and gender lines.

According to former A&M history professor Henry Dethloff’s “A Centennial History of Texas A&M,” 150 women were enrolled at the college that first fall, and their numbers continued to climb in the years that followed: “… change was clearly in the air,” Dethloff wrote.

The Corps of Cadets, however, remained all-male despite efforts from a number of interested female students and some parents.

By the 1970s, the prospect of admitting women to A&M’s military training programs was still highly controversial. But according to Aggie historian John A. Adams ’73, it was starting to look like it might be inevitable — especially as more women entered the armed forces and began to fill a wider variety of roles.

In “Keepers of the Sprit,” Adams’ book on the history of the Corps, he notes that integration of college ROTC programs was fast becoming a high priority for the military, with special attention paid to large, federally-funded institutions like A&M and the service academies.

Sure enough, by 1973, Corps Commandant Col. Tom Parsons was receiving “repeated inquiries from the Department of the Army on the status of women in the Corps of Cadets,” Adams wrote. And of course, the passage of Title IX the year prior had not escaped the notice of Parsons or Texas A&M President Jack K. Williams.

“Williams, as well as the Commandant, many alumni, and many of the cadets in command positions knew that it was only a matter of time before the new federal guidelines were broadened and enforced for all college activities,” Adams wrote.

With that in mind, Williams and Parsons made a significant decision: Texas A&M would become the first major military college in the nation to admit women into its officer training program.

“This was before any women were in any of the service academies, or the Virginia Military Institute or the Citadel,” said Roxie Pranglin ’78, who joined A&M’s first-ever class of female cadets in the fall of 1974. “We were the first Corps of Cadets-type environment that allowed women to participate, and was it done perfectly? No. But I believe it was done with good intentions.”

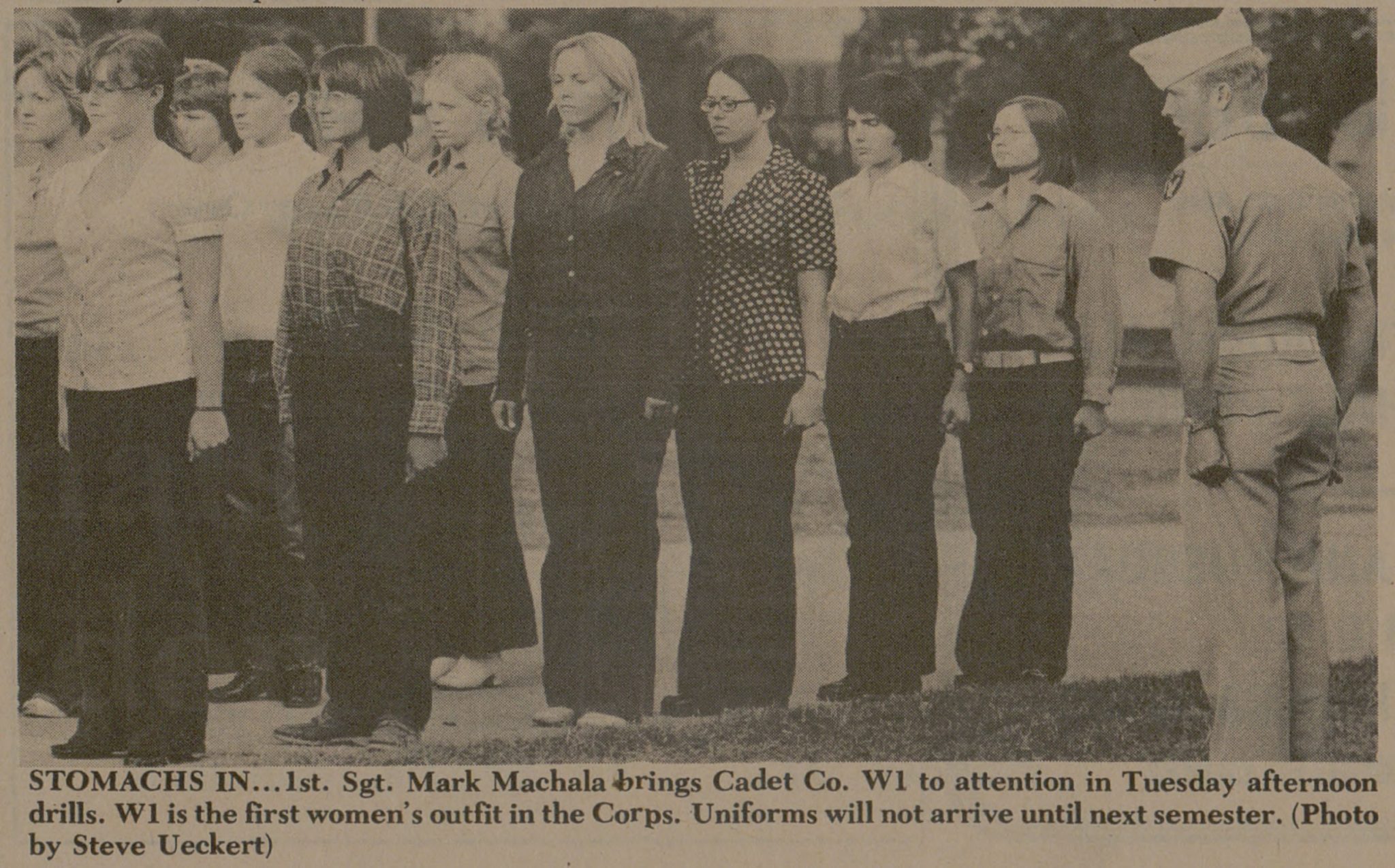

The change had come swiftly. Juniors on Corps staff during the previous school year were tasked with preparing a detailed plan for the integration of women. They called it “The Minerva Plan” after the Roman goddess of wisdom, justice and war. When Pranglin and the other women arrived on the Quad that first semester, they were organized into the all-female Company W-1: “Minerva’s Finest.”

A Rocky Start

The transition into Corps life was not a particularly seamless one, Pranglin said. The women of W-1 didn’t get uniforms until the following semester, and they were not able to live on the Quad until the following school year.

“Our numbers fluctuated each day, people would join up and people would drop out, and we lived all over the place, so there was a lot of coming and going in those first weeks and months,” said Pranglin, who later went on to a 30-year career in higher education. “Everyone was really trying to figure out what to do with us, so the rules kind of changed regularly.”

One early point of contention was whether the women should be allowed to “whip out” — a traditional introduction and handshake between cadets. Pranglin said many male cadets would just leave the women standing with their hands outstretched.

“If they just refused to meet you, that was one thing,” she said. “When they then proceeded to tell you what they thought of you and how you were ruining the Corps of Cadets and Texas A&M, that was another.”

Still, the small band of women was not without allies, both on the Quad and off. The most obvious and visible were W-1’s first officers — male upperclassmen who volunteered to lead the female cadets through their tumultuous first years.

Their original commanding officer, Steven “Don” Roper ’75, said that while it didn’t make him very popular at the time, he remains proud of the work he and others did during those initial semesters.

“My goal was, at the end of the year, to basically walk away standing as an outfit,” Roper said. “And we did more than that — we excelled in certain areas. We certainly excelled in unity, and we excelled in learning how to protect each other’s backs, because that’s exactly what we did.”

The Push For Progress

In the spring of 1975, W-1 made its first public debut in full uniform, marching across Simpson Drill Field at the annual Military Day review. They received a standing ovation, Roper said.

“That was a huge part of the year for us,” he recalled. “Everything that we put into it had become worth it on that day.”

The women of W-1 would continue to face pushback, especially when they started living on the Quad the following semester. But as Pranglin’s classmate Ann Sheridan ’78 recalls, they were starting to find their footing.

“You learned that the friendly face isn’t necessarily friendly, but the guy chewing you out, if they’re trying to make you better, is your friend,” said Sheridan. She later served four years on active duty in the U.S. Army before moving into the Army reserves and pursuing a career as a professional engineer.

Slowly but surely, the women of the Corps were making new opportunities for themselves, too. The Women’s Drill Team was formed and soon found considerable success in competition: “We were good,” Pranglin said.

It was on that team that she and Sheridan became acquainted with Melanie Zentgraf ’80, a W-1 underclassman who later became a founding member of Squadron 14 — a second all-female outfit specifically for Air Force cadets.

“The class of ’80 wanted to be exceptional,” Sheridan recalls, and Zentgraf fit the bill. “She was tall, she was physically capable, she learned very quickly, she was incredibly intelligent.”

Zentgraf also wanted to join the Color Guard, one of several special units in the Corps including the Aggie Band and Ross Volunteers that had remained off-limits to female cadets.

“She tried out and the class of ’79 told her, ‘We didn’t think you would do well because you’re a girl, but you are the best candidate,’” Sheridan said. “But then my class said it ‘wasn’t military’ for a woman to be on Color Guard.”

Zentgraf was denied membership. And after repeated attempts to deal with the issue internally, her experience ultimately led her to take legal action against the university. A 1979 class-action suit argued that Texas A&M was violating Title IX by permitting sex discrimination in the Corps’ special units.

From the very start, the case was both high-profile and historic. When the U.S. Department of Justice moved to join the suit later that year, an Associated Press report noted it was the first time the federal government had taken action to enforce Title IX since the law was passed.

As Pranglin recalls, the suit was incredibly divisive, and for Zentgraf, the backlash was overwhelming.

“Melanie Zentgraf had a hard time,” Pranglin said. “And whether anyone agrees that she should have filed the lawsuit or not, I can tell you for sure that nothing changed until she did.”

In 1985, long after Zentgraf had graduated, was commissioned and entered the U.S. Air Force, the Texas Attorney General agreed to a settlement that would require A&M to actively embrace female participation in all areas of the Corps — special units included.

That same year, Abat and others were allowed to join and march with the Aggie Band, and in 1986, A&M had its first female Ross Volunteers: Mandy Schubert ’87 and Nancy Hedgecock ’87.

As Zentgraf told the Associated Press on the day of the settlement, “It’s over, but it’s just begun.” Zentgraf passed away from cancer in 2020, after a long and successful career flying for FedEx.

Marching Forward

Sure enough, Abat’s time in the Corps and band helped pave the way for further integration. The Aggie Band’s A-Battery became the first co-ed outfit, and their living quarters became the first integrated dorm facility when Abat moved in with the rest of her squadmates in 1986.

By 1990, the all-female W-1 and Squadron 14 were eliminated, and co-ed units started to become the norm.

“I think we do a disservice to young people if they’re not in the midst of both genders, because they’re going to have to deal with both genders in the real world,” Abat said. “It was a great thing and the right thing for the university.”

She said her time in the Aggie Band also helped to dispel the myth that integrating the Corps and its special units would dilute their distinct character.

“The reality is, change is always difficult,” Abat said. “I think if you distill it down, that’s what people were afraid of, that if women came into the band, it would turn into just any other band.”

But as Abat notes, “the band did not fall apart.” And neither did the rest of the Corps. More diverse than ever, it continues to train cadets for whatever may await them after graduation, just as it did for those trailblazing women of the 1970s and 80s.

“If you look at the history of these women, 15 years down the road, we already had five full colonels,” Roper said. “Other women have taken on very strong roles, everything from the Environmental Protection Agency right on down into business and the clergy. Each of those places they went benefited from having this particular group of women be part of their community.”